SOUTHEAST OREGON WILDFIRE RESILIENCE PROJECT

THE LONG DRAW WILDFIRE WAS STARTED BY A LIGHTNING STRIKE JULY 8, 2012 AND BURNED 557,648 ACRES IN SOUTHEASTERN OREGON.

In July 2014, a lightning storm recording thousands of strikes ignited several fires, which merged to create the Buzzard Complex Fire, named for Buzzard Butte about 45 miles southeast of Burns, OR.

It left scorched earth and dead or injured cattle in its wake, burning a total of 396,017 acres owned by the Oregon State Department Lands, the Bureau of Land Management, and private ranchers.

Just two years prior in 2012, the Miller Homestead Fire and the Long Draw Fire burned 160,801 acres and 557,648 respectively.

These catastrophic fires left a destructive mark burning through vital sagebrush steppe habitat, destroying grazing land, wildlife habitat, and foraging ground. The fires killed and injured livestock and wildlife and damaged private property at an immense cost to the local landowners.

Living with the devastation of these and other wildfires in southeast Oregon, the folks who deal with wildfires in Harney County decided they wanted to be more proactive. To play offense not defense, when it comes to better preparing for the mounting threat of megafires. This meant forming the Harney County Wildfire Collaborative (HCWC) in 2014, in partnership with Rangeland Fire Protection Association members, federal, state, and county employees, tribal members, conservationists, scientists, and local ranchers. A diverse group of stakeholders coming to the table to determine how to make sagebrush steppe landscapes more resistant and resilient to unexpected fire.

The goal was to provide a platform where everyone could have an equal and valued seat at the table, making it possible for the group to formulate a more effective and comprehensive wildfire strategy with the intent of making the land more resistant to fire as well as resilient in the aftermath of fire.

Partners of the Harney County Wildfire Collaborative at a discussion stop during a July 2022 field tour

in the Stinkingwater Mountains of southeast Oregon.

In 2018, the collaborative identified the Stinkingwater Mountains near Burns and Crane, an area which sustained considerable wildfire damage from the Buzzard Complex, as a project of focus. The Stinkingwater Mountains Restoration & Fire Resilience Project project targets 312,000 acres of private, tribal, state, and federal lands for active restoration and suppression management efforts with the end goal of creating a landscape that’s healthy, more tolerant to fire, and provides both forage for livestock and habitat for wildlife.

Rancher Rick Habein, former owner of the Lamb Ranch, participating in the

Harney County Wildfire Collaborative July 2022 Stinkingwater Mountains field tour.

In 2021, Oregon Senate Bill 762 passed, allocating $220 million to help Oregon modernize and improve wildfire preparedness through three key strategies: creating fire-adapted communities, developing safe and effective response, and increasing the resiliency of Oregon’s landscapes. Because of the groundwork laid by the Harney County Wildfire Collaborative, the Harney County Wildfire Collaborative applied for and secured more than $5 million to address wildfire issues in the southeast corner of Oregon in Harney and Malheur counties through the Southeast Oregon Wildfire Resilience Project.

More than 50 partners of the Harney County Wildfire Collaborative during a field tour in the Stinkingwater Mountains July 2022.

Thanks to the additional funding, the wildfire resilience work already in progress for the Stinkingwater Mountains Restoration and Fire Resilience Project was expanded to encompass the Beaver Tables area and land near Juntura and Jonesboro, expanding all the way into Malheur County.

The first round of work, completed in 2023, consisted of critical fuel treatments to enhance wildfire resilience across more than 80,000 acres of Southeast Oregon’s sagebrush steppe. But in the middle of 2023 the drivers of this project received exciting news. Their application for further funding had been approved, which meant they had an additional $3.8 million coming to them to help implement wildfire resiliency treatments on a further 22,000 acres of public and private land in Harney and Malheur Counties. The work that began this spring marks round two of the SOWR project, an effort which will continue through June of 2025.

About the Southeast Oregon Wildfire Resiliency Project.

THE VULNERABILITY OF THE SAGEBRUSH STEPPE

Chad Boyd, Agricultural Research Service Range Scientist and Research Leader distinguishing between invasive annual grasses and perennial shrubs in the sagebrush sea ecosystem and what conditions aid wildfire resiliency.

The vast sagebrush steppe dominates the landscape of Eastern Oregon. It is a land of extremes receiving less than 12 inches of precipitation per year and often reaching temperatures of more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer. Winters are bitterly cold and harsh, and summers are prone to drought. The high variability of soil, vegetation and production can hamper restoration efforts and contribute to the fragility of the landscape.

Even so, the sagebrush steppe is home to a diverse array of wildlife including mule deer, Rocky Mountain elk, pronghorn, greater sage grouse, pygmy rabbits, dozens of raptor and songbird species, and reptiles.

While wildfire has always been part of the lifecycle of the sagebrush steppe, wildfires have consistently burned hotter and faster than those of the past. They also create the perfect storm for invasive annual grasses to take hold and push out perennial grasses. There is less habitat, food, and cover for wildlife to rely on for survival.

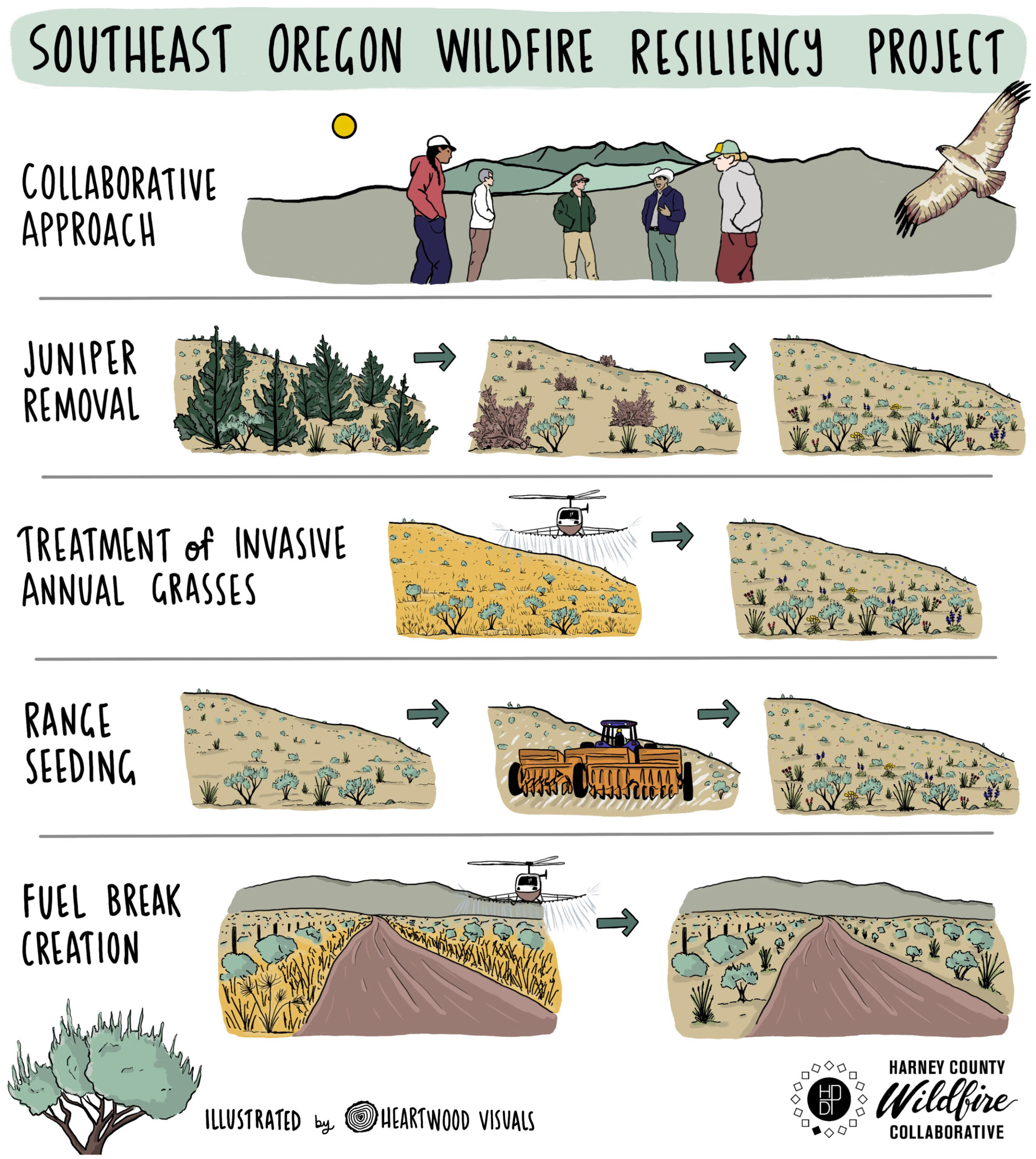

JUNIPER TREE REMOVAL

Though the Western Juniper is native to the Harney Basin, its encroachment into the sagebrush steppe landscape within the last century has created a real impact where people recreate, live and work.

Where junipers were previously relegated to rocky outcroppings that were resistant to fire, they now occupy about 3.7 million acres in Oregon. This can be traced back to restrictive fire suppression practices, the introduction of livestock grazing, and juniper seeds being ingested and spread by birds or naturally through wind, water, and soil erosion.

Because junipers consume large amounts of water, they are in direct competition with other native species for space, water, sunlight, and soil nutrients. This causes shrubs, forbs, and native grasses to die off, creating a lack of vegetation, habitat and nutrients for wildlife and livestock. For example, studies have shown greater sage grouse will start to avoid areas where juniper has reached a 3 to 4 percent spatial occupancy. In addition, after native vegetation dies off, the area underneath the juniper canopy will often fill in with invasive annual grasses, which burn quickly and easily in the event of a wildfire.

A water deprived sagebrush ecosystem on the left due to Juniper consuming the majority of the water available.

A healthy sagebrush ecosystem that doesn’t have to compete with Juniper for water.

To combat juniper encroachment, Harney County Wildfire Collaborative partners are targeting strategic sites for juniper removal for restoration work through the Southeast Oregon Wildfire Resiliency Project.

Jason Kesling, District Manager with the Harney County Soil and Water Conservation District describing the

habitat and wildfire resilience benefits of cutting Juniper.

Progress is happening, and some areas where juniper has been removed boast an increased presence of groundwater in the form of springs and healthier riparian zones. The removal of thousands of acres of junipers is helping to create a more resilient and fire-resistant landscape. In the long run, the increase in native perennial plants will facilitate the return of sagebrush to many areas in Eastern Oregon.

Juniper cut on more than 900 acres of private ranch land is making it possible for the native plants and trees to access the water once used by the invasive Juniper. The access to this water is helping the Aspen trees, Pecks Indian Paintbrush, Silky Lupine, Western Meadowlark and many more plant, tree and wildlife species of this habitat thrive.

TREATING INVASIVE ANNUAL GRASSES

Another component of the Southeast Oregon Wildfire Resiliency Project involves treating invasive annual grasses. These non-native grasses typically originated from Eurasia and have become established in western North America where they are well adapted to the climate and soil. Such plants include Cheatgrass, Medusahead rye and Ventenata.

Medusahead, an invasive annual grass, grows and spreads rapidly making it highly competitive with native species and a threat to the sagebrush ecosystem.

Chad Boyd, Agricultural Research Service Range Scientist and Research Leader about how invasive annual grasses create a consistent bed of fuels for wildland fires and why they are a treatment target to improve wildfire resiliency in southeast Oregon.

Invasive annual grasses intercept moisture before it reaches deeper-rooted native perennials and create a thatch layer that can smother native perennial plants. By outcompeting the native perennials, the invasive annual grasses fill the natural space between sagebrush plants across the Great Basin creating a carpet of fuel, which when ignited by lightning, allows wildfire to spread rapidly.

Josh Hanson, High Desert Partnership’s Forest & Ecological Coordinator describing the invasive annual grass issue on rangelands. Josh is the coordinator for the Harney County Wildfire Collaborative.

Two common herbicides, Imazipic and Indaziflam, are used to prevent the spread of these invasive annual grasses. The herbicides pose no threat to wildlife or livestock and have been vetted by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Oregon Department of Agriculture for environmental safety. The herbicide application process is strategic; pre-emergent herbicides are sprayed in the late fall because they need moisture to bind in the soil to prevent seed germination.

Treatment areas will be monitored alongside untreated sites for long-term comparison. Project managers believe that the herbicide will provide four to five years of cheatgrass and Medusahead control. This will allow the existing perennial plant community to flourish. Ultimately, the goal is to make the landscape more resistant to wildfire and more resilient in its aftermath while allowing native grasses to provide food and shelter to wildlife and livestock.

A High Desert Partnership crew monitoring a site treated by the herbicide Indaziflam.

CASE STUDY: BENTZ RANCH

On the Bentz Ranch in Malheur County approximately 14,000 acres of invasive annual grasses were treated with the herbicide Rejuvra. A family member, Erika Fitzpatrick who is a part of the family ranch and operates Mesa Communications, documented their experience throughout this project and the impacts to the landscape. These before and after images from aerial treatments put on display a stark change in the volume of invasive annual grasses. Envu, the maker of Indaziflam (Rejuvra), claims this product will provide a multi-year result. Time and monitoring of the treatments will determine the results for this acreage and next steps toward reducing invasive annual grasses and the fuel they provide for wildfires.

“Our goal was to interrupt the trend of these ever-spreading invasive annual grass, especially Medusahead, to increase forage production for both wildlife and livestock, reduce fine fuel and fire risk, and improve the resilience of this landscape for years to come. We are incredibly encouraged by the results so far.” – Linda Bentz

SEEDING THE

SAGEBRUSH STEPPE

While harmful invasive grasses are being targeted for removal, project managers are also looking to bolster native perennial grasses through seeding of strategic sites.

Range seeding is the intentional introduction of seed of a desired plant species to the rangeland environment. Perennial bunchgrasses are native to the sagebrush steppe and can help the landscape bounce back after a wildfire.

There are some introduced species of plants that can also improve the landscape to be more fire resilient. In some areas when perennial bunchgrasses fail to reproduce from seed, it can be helpful to introduce species such as crested wheatgrass, which doesn’t need as much moisture to thrive.

EcoSource Native Seed & Restoration is one Harney County Wildfire Collaborative partner who is currently doing native rangeland seeding in Harney County. They use site-specific data to develop a seeding plan to restore ecological function to targeted areas. In addition to restoration, EcoSource is also gathering native seed to grow locally to build a supply of locally sourced seeds for future restoration projects.

Herbicides kill harmful invasive annual grasses, but it’s important that those areas are also reseeded with beneficial perennial grasses, otherwise the annual grasses will continue to encroach. Rangeland seeding has produced positive results for many areas in the Southeast Oregon Wildfire Resiliency Project, and rangeland scientists are developing seeding technologies and varieties of native species that they hope will continue to increase the odds of seeding success.

WORK CONTINUES

The Southeast Oregon Wildfire Resiliency Project is complete but the work of the wildfire collaborative continues. Wildfires are part of our lives and the landscape and as a result, the Harney County Wildfire Collaborative will always have work to do. In this era of catastrophic wildfires, the collaborative is committed to preventing wildfires whenever possible and restoring the land when they do occur.

Jeff Rose, District Manage with the Bureau of Land Management about benefits of the Harney County Wildfire Collaborative and Southeast Oregon Wildfire Resiliency Project.

“This funding increased the scale of work that can happen to help the Harney County Wildfire Collaborative partners reach a goal of building a wildfire resilient landscape. Just as wildfire knows no boundaries this work has impacted public, private and tribal lands while feeding the economies of small frontier communities in southeast Oregon.” – Autumn Muir, Harney County Wildfire Collaborative partner and Project Manager, Uplands Coordinator for the Lake County Umbrella Watershed Council

SOUTHEAST OREGON WILDFIRE

RESILIENCY PROJECT BY THE NUMBERS

Land treated for the Southeast Oregon Wildfire Resiliency Project was a mix of private (38,348 acres), tribal (500 acres), state (7,909 acres) and federal (34,954 acres) in 2 Oregon counties, Harney and Malheur.

One collaborative, Harney County Wildfire Collaborative with more than 140 partners from around the state of Oregon planned and implemented the project.

The Southeast Oregon Wildfire Resiliency Project was made possible by funding from Oregon Senate Bill 762, administered by the Oregon Department of Forestry.

ABOUT THIS STORY

• Written by Lauren Brown

• Video by Kevin Raichl, Visual Thinking Northwest and Erika Fitzpatrick, Mesa Communications

• Illustration by Carrie Frickman, Heartwood Visuals

• Still images by Brandon McMullen, BG Michael Images; Erika Fitzpatrick, Mesa Communications and High Desert Partnership staff

• ArcGIS Story map built by Emily O’Connor, High Desert Partnership

• Web development by Focus Media

• Special thanks to all the interview participants: Chad Boyd, Rick Habein, Josh Hanson, Jason Kesling and Jeff Rose.

• Written by Lauren Brown

• Video by Kevin Raichl, Visual Thinking Northwest and Erika Fitzpatrick, Mesa Communications

• Illustration by Carrie Frickman, Heartwood Visuals

• Still images by Brandon McMullen, BG Michael Images; Erika Fitzpatrick, Mesa Communications and High Desert Partnership staff

• ArcGIS Story maps built by Emily O’Connor, High Desert Partnership

• Web development by Focus Media

• Special thanks to all the interview participants: Chad Boyd, Rick Habein, Josh Hanson, Jason Kesling and Jeff Rose.

CONTACT

Aaron Johnston, Forest & Range Ecological Coordinator

aaron@highdesertpartnership.org

© High Desert Partnership

CONTACT

Aaron Johnston, Forest & Range Ecological Coordinator

aaron@highdesertpartnership.org

© High Desert Partnership

CONTACT

Aaron Johnston

Forest & Range Ecological Coordinator

aaron@highdesertpartnership.org

© High Desert Partnership